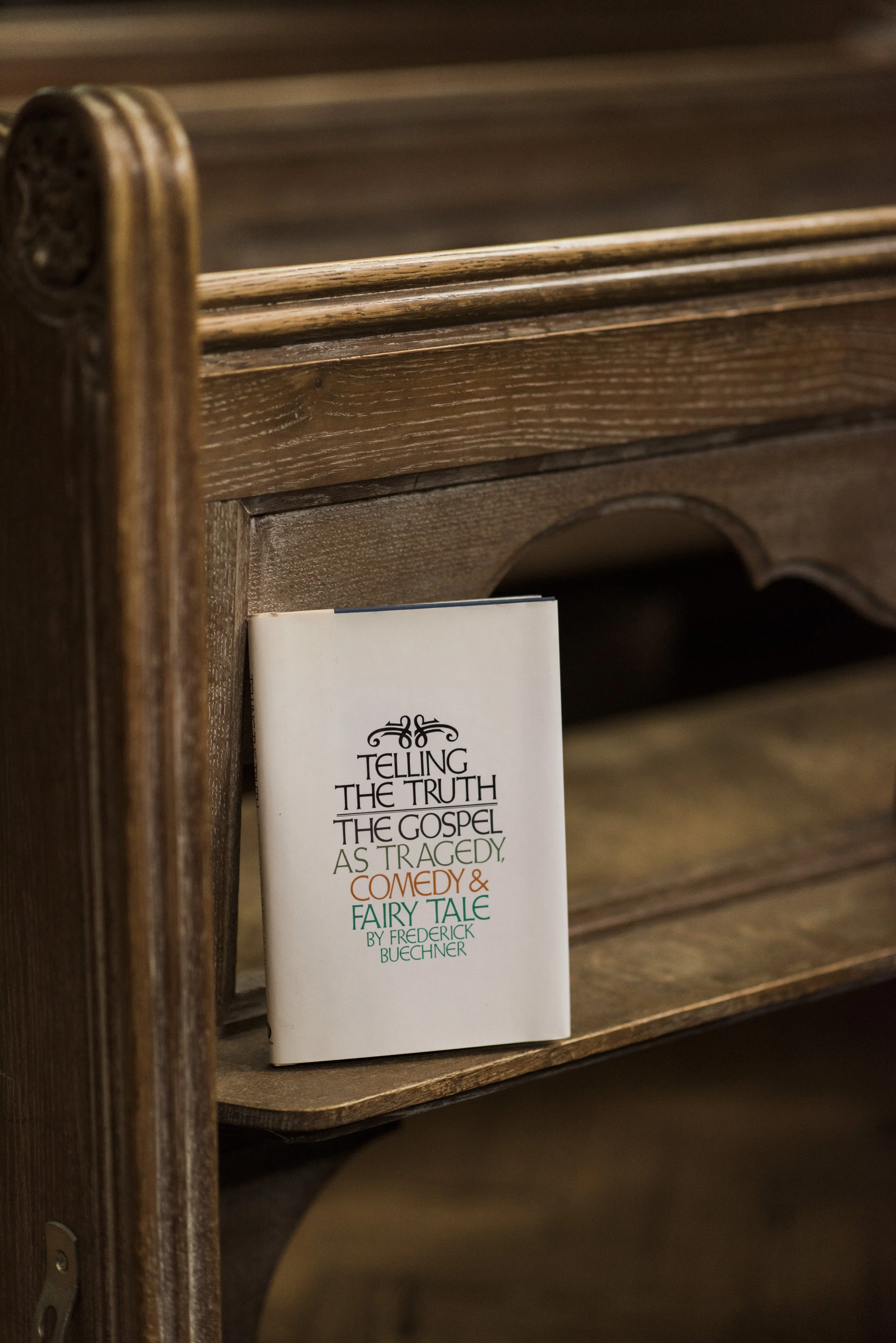

I recently returned to one of my favorite Buechner books: Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale (1977). I first read this book about ten years ago, and have dipped into it several times since then, but as I read through it again something new caught my attention. There is a passage in which Buechner is describing a church congregation in the moments before the preacher begins his sermon. There they sit — some bored, some struggling, some a little desperate, but all expectant — waiting for him to work a miracle.

...the miracle they are waiting for is that he will not just say that God is present, because they have heard it said before and it has made no great and lasting difference to them, will not just speak the word of joy, hope, comedy…but that he will somehow make it real to them. They wait for him to make God real to them through the sacrament of words as God is supposed to become real in the sacrament [of bread and wine].[1]

The phrase in that last sentence, ‘the sacrament of words,’ stopped me in my tracks. It was a phrase I’d heard before, but had always thought of as a way of emphasizing the importance of the sermon — especially in the Reformed tradition in which I was raised. The Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer thought of preaching as the third sacrament, writing that the ‘word of the sermon is the incarnate Christ himself.’[2]

In Buechner’s hands, though, the phrase spoke to me in a different way. I suspect this is because, while he is describing a sermon in this imagined scene, it comes in the broader context of his book-long meditation on how stories and poetry can speak the truth about reality with great profundity and power. In other words, how they can preach.

As a person who spends much of her time reading and writing, this idea intrigued me. It also started me wondering what it is about words that we might consider to be sacramental. The idea that Buechner unfolds in Telling the Truth, and indeed in many other books, is that the reality of God is incarnate in our lives. As the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, so God continues to speak in the embodied reality of our day-to-day existence — the ‘alphabet of our lives.’

The task of the preacher is not simply to tell us about God, but to make him real to us by drawing on words and images ‘that help make the surface of our lives transparent to the truth that lies deep within them, which is the wordless truth of who we are and who God is and the Gospel of our meeting.’[3] Such words are revelatory. They can transform our perception of reality, sometimes simply by giving us courage to face it at its most bleak.

Buechner is one of many writer-preachers down the years who have regarded words as in some sense sacramental. Take, for example, the Victorian writer and preacher George MacDonald (Buechner affectionately refers to him as ‘the great George MacDonald’). For MacDonald, the miracles of Christ symbolize a wider glorifying of all created things: Christ ‘turns not only water into wine, but common things into radiant mysteries, yea, every meal into a eucharist.’[4] This transformation is not a change in the things themselves, but in our perception of things. With such transfigured vision, nearly everything has the potential to be a sacrament, including books. In MacDonald’s novella The Portent (1864), the narrator tells the reader that for him books are ‘a kind of sacrament—an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace; as, indeed, what on God’s earth is not?’[5]

MacDonald’s recognition of the miraculous nature of the everyday resonates with the work of another writer (and sometimes preacher) Marilynne Robinson, whose novels gently trace the mysterious presence of grace within the ordinary. In Gilead (2004), the minister John Ames reflects on the constancy and extravagance of God, for ‘[w]herever you turn your eyes the world can shine like transfiguration. You don't have to bring a thing to it except a little willingness to see. Only, who could have the courage to see it?’[6]

For some people, especially the disillusioned, courage is required to ‘acknowledge that there is more beauty than our eyes can bear.’[7] For others, courage is needed to tell the truth about the moments when it is difficult to discern grace, or indeed any hint of God’s presence in our lives. For Buechner, these honest words are also sacramental, and are found less in the sermons of priests or ministers than in the words of the poets, playwrights, and novelists. He writes:

What gives such power to the preaching of these artists and what makes them voices that all preachers would do well to learn from is that they are willing to appall and bless us with their tragic word—to speak out of the darkness and weep as Jesus wept because maybe only then can the reality of the other word become real to us…They preach the word of human tragedy, of a world where men can at best see God only dimly and from afar, because it is truth and because it is a word which must be spoken as prelude if the other word is to become sacramental and real, too, which is the word that God has overcome the dark world…[8]

The incarnation of the Word, the suffering Servant, speaks not only of God’s continued presence with us in midst of our darkness and pain, but of his apparent absence: ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ (Matt. 27.46). Somewhat paradoxically, then, for God to be made real in the sacrament of words the truth must be spoken not only about the joy and beauty in which we might sense his presence, but also about the tragedy and pain in which he feels absent. ‘The weight of this sad time we must obey / speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.’[9]

Shakespeare’s King Lear, Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, Hopkins’s ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’, these are all works Buechner draws on to illustrate the sacrament of honest words. Hopkins is a poet whose work has often been a source of grace for me, from his exuberant recognition of the presence of God in nature to the mental and spiritual anguish of his ‘Terrible Sonnets’.

I have a distinct memory of my first encounter with a sonnet of Hopkins’s in which, in a kind of exhaustion from the mental torture he is experiencing, the speaker addresses himself with great compassion. I quote it in full here:

My own heart let me more have pity on; let

Me live to my sad self hereafter kind,

Charitable; not live this tormented mind

With this tormented mind tormenting yet.

I cast for comfort I can no more get

By groping round my comfortless, than blind

Eyes in their dark can day or thirst can find

Thirst's all-in-all in all a world of wet.

Soul, self; come, poor Jackself, I do advise

You, jaded, lét be; call off thoughts awhile

Elsewhere; leave comfort root-room; let joy size

At God knows when to God knows what; whose smile

'S not wrung, see you; unforeseen times rather—as skies

Betweenpie mountains—lights a lovely mile.

I encountered this poem at a time when I, too, was experiencing the tangle of a ‘tormented mind tormenting yet,’ and, like Hopkins’ speaker, not showing myself much pity. Part of what spoke to me in this poem was not only a discovery that I was not alone in my experience, but the particular mode in which the poem expresses this experience.

As I read this poem aloud to myself I found it captured not just the idea of what I was feeling, but the affective experience of it. As the literary critic Michael Hurley points out, ‘poetry invites us to know through the experience of the tumble, push, pull and swell of its prosody.’[10] Identifying not only with the idea but the movement of this poem allowed me to move with the speaker from the cramped, relentless circling of ‘this tormented mind / With this tormented mind tormenting yet,’ into the gentle expansion that occurs as the poem progresses: the affectionate address to the weary self and the encouragement to allow room for comfort to grow and unexpected joy to shine.

My experience of reading Hopkins’ poem articulates something of what I think Buechner means when he writes of the sacrament of words. He was well aware that poetry, drama, and stories all offer a unique mode of speaking the truth, for they make things real to us in this affective, embodied way. They are, in that sense, incarnate. He writes of the Old Testament prophets putting words to both ‘the wonder and the horror of the world, ‘but because these words are poetry, are image and symbol as well as meaning, are sound and rhythm, maybe above all are passion, they set echoes going the way a choir in a great cathedral does, only it is we who become the cathedral and in us that the words echo’.[11]

It is a beautiful image, not only of the words themselves, but of we who hear them as sacred spaces resonating with a kind of heavenly music. Listen to these words and listen to your lives, Buechner urges us, ‘Listen to the sweet and bitter airs of your present and your past for the sound of [Christ]’ for ‘the words he speaks are incarnate in the flesh and blood of our selves and of our own footsore and sacred journeys.’[12]

In my own journey, Buechner’s words have been the kind of sacrament he describes in Telling the Truth. It is not always easy for me to see God’s presence in this world of violence and injustice. But Buechner’s presence as a fellow-traveler who ‘speaks what he feels and not what he ought to say’ has often helped me to speak honestly with myself and with God. By telling the truth about pain and struggle, Buechner earned my trust, so I can often believe alongside him that the joyful ‘catch of the breath, that beat and lifting of the heart near to or even accompanied by tears…is the deepest intuition of truth that we have.’[13] And that is indeed something of a miracle.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Thank you for reading The Buechner Review. If you would like to receive future articles in your email inbox you can sign up here.

Works cited:

[1] Frederick Buechner, Telling the Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy Tale (New York: Harpercollins, 1977), p.40.

[2] Jens Zimmerman, ‘Reading the Book of the Church: Bonhoeffer’s Christological Hermeneutics,’ Modern Theology 28:4 (October 2012), pp. 774-775.

[3] Buechner, Telling the Truth, p.23-24.

[4] George MacDonald, The Miracles of Our Lord (London: Strahan, 1870), p.18.

[5] George MacDonald, The Portent: a story of the inner vision of the Highlanders, commonly called the second sight (London: Smith & Elder, 1864), p.82.

[6] Marilynne Robinson, Gilead (London: Virago, 2004), p.279-280.

[7] Ibid., p.281.

[8] Buechner, Telling the Truth, p.47

[9] William Shakespeare, King Lear, 5.3.392-93. Buechner frequently quotes these lines in Telling the Truth, and entitles his book on Hopkins, Chesterton, Twain, and Shakespeare Speak What We Feel (Not What We Ought to Say) (2001).

[10] Michael D. Hurley, ‘How Philosophers Trivialize Art: Bleak House, Oedipus Rex,“Leda and the Swan”.’ Philosophy and Literature, vol. 33, no. 2, 2009, pp. 121.

[11] Buechner, Telling the Truth, p.19, 21.

[12] Buechner, The Sacred Journey, p.77-78.

[13] Buechner, Telling the Truth, p.98.

Sign up here to receive articles in your inbox