September 2025

“Ministering to an Invisible Congregation”: Frederick Buechner’s Vision of Fiction

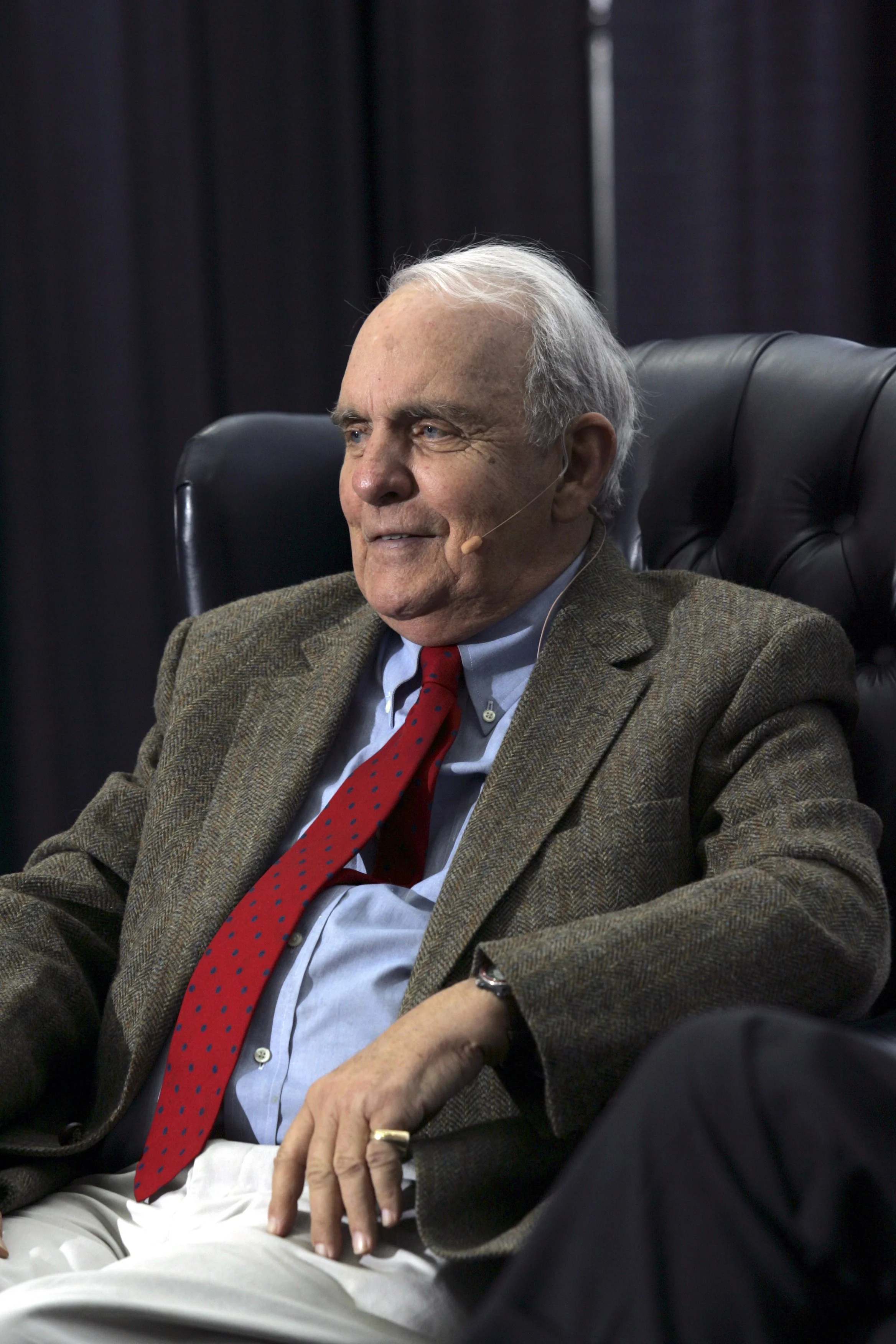

How exactly will Frederick Buechner be remembered? And which parts of his vast collection of writings will be most cherished by readers? In the years since Buechner’s death in August, 2022, there have been many different answers to such questions. The New York Times, in its obituary, characterized him, with comical understatement, as a “novelist with a religious slant”; Christianity Today paid him the dubious compliment of being a “writer’s writer”; and Michael Maudlin, Senior Vice-President and Executive Editor at Harper Collins, positioned Buechner as “a unique figure, a literary figure.” His legacy is of course still working itself out, and the way in which he will be remembered is not yet clear. Buechner produced a vast amount of writing in his ninety-six years, across many genres, including essays, memoirs, sermons, art and literary criticism, lectures, and poems. So much of this writing contains extraordinary insights set forth in his characteristically nimble and lively prose. But it is Buechner’s novels that strike me as being at the heart of his writerly project. As I see it, he was indeed a “literary figure” first and foremost. For all of his achievements in other genres, I think that Buechner deserves to be remembered primarily as a novelist, who had an utterly eccentric and compelling vision of what the novel form is capable of doing.

In making such a claim, I am hardly going out on a limb. I am actually following Buechner himself, who told an interviewer in 1983 that of all the things he would want to be remembered for, he “would choose the fiction.”[1] And I am also following the lead of one his greatest and most famous admirers, the writer Annie Dillard, who calls Buechner’s novels “his masterpieces.”[2]

And masterpieces they are. Buechner’s novels are impossibly strange and beautiful and breathtakingly original. They offer life-giving, mind-altering experiences, and are filled with treasures waiting to be discovered by an attentive reader. Buechner had a thoroughly sacramental vision of literature that is full of the highest ambition and aspiration — one that very few other novelists have approached. From A Long Day’s Dying, published in 1950 to 1998’s The Storm, Buechner spent half a century experimenting with what the novel might be able to hold, express, and make possible for both author and reader. Many of his novels are radiant jewels that were never really properly appreciated during his lifetime and may well be soon forgotten, outside of a small but devoted following.[3] Perhaps they are destined to be cult classics rather than actual classics, inspiring fervid devotion among a small coterie of readers but never reaching a wider audience. If this is indeed the fate of his fiction, it would be an immense shame.

In this brief piece, I want to make a case for Buechner’s extraordinary, idiosyncratic novels, by looking first at what he thought it meant to be a writer; then at what he thought the novel form made possible; before finally thinking through what he asked of us as readers.

I.

What did Buechner think it meant to be a novelist? While many writers express a sense of calling and vocation, and see their task in noble terms, it is hard to think of a higher vision than the one Buechner articulated. After being ordained in the Presbyterian Church and serving as a chaplain at Phillips Exeter Academy, Buechner left the more straightforward and recognizable paths of ministry in order to serve and minister to readers. It is striking that he describes his work as a novelist in just these terms, seeing his artistic vocation as a genuine form of “ministry” in which he might communicate nothing less than the glory and mystery of God. More startlingly still, Buechner thought of novel writing as a “priestly craft that involves a special kind of sacrifice and discipline” in which he would serve an “invisible congregation” made up of distant readers.[4]

What other novelist would dare conceive of his or her art as a “priestly craft”? Some others might invoke a level of sacrifice and discipline, but even these terms mean something distinctive in the Christian tradition, implying as they do rigorous forms of obedience and ascetism. Even the extravagant literary manifestos and artistic agendas set forth by the high modernists of the early-twentieth century seem downright modest in comparison to Buechner’s articulation, which is either the most grandiose and overweening ever set forth or else reflective of a truly inspired, holy calling. At different points in his career, he himself seems to have been unsure of which was the case. It goes without saying that it was — and is — a spectacularly risky proposition. Both success and failure take on unfathomably large dimensions within Buechner’s project. Either the reader will recognize these novels as inspired texts full of reflected glory and light, as nothing less than “priestly” mediations between God and humanity, or else they will be dismissed out of hand as hubristic hogwash.

As is no doubt obvious, I myself am firmly in the first camp. Buechner’s novels have been true blessings and gifts to me. They have lit up parts of myself I didn’t realize existed, offered unexpected insights and moments of clarity, as well as opening up new possibilities. They have given form and shape to my innermost imagination, and I am convinced that a few of them — particularly Godric (1980) and Brendan (1987) — have indeed ministered to me. I see Buechner’s novels as what Stanley Cavell calls “perfectionist friends”: guides that provoke and encourage, and “whose conviction in one’s moral [and also spiritual!] intelligibility draws one to discover it, to find words and deeds in which to express it.”[5] As strange as it may sound, these novels really have been friends and guides.

It is difficult to translate the experience of reading these novels. Reviewing The Son of Laughter (1993), Dillard herself was left searching for words to describe the strange, holy experience of reading Buechner’s version of the Genesis story of Jacob, which she said “sounds as though the writer is holding onto a lightning bolt.”[6] There is a power and heft to his fiction that does indeed feel elemental and hard to account for. “What other novelist’s worlds do SOULS inhabit?” Dillard wondered elsewhere, noting the remarkable fact that “souls live” in Buechner’s fiction. “What other writer” she asks, “gives breathing room to SOULS?”[7] Precisely. How often do we encounter souls in fiction? As someone who spends my days writing on literature and teaching students how to comprehend and receive its strange gifts, I feel I should be able to analyze and comprehend what Buechner is doing in these eccentric, mystical, and enormously powerful novels. Instead, I can really only gape in wonder.

II.

Since I am tongue-tied and powerless to explain their peculiar force, it seems far more helpful to turn to Buechner’s own sense of what the form can make possible. What kinds of experiences and possibilities did he take it to afford, for both writer and reader? Here again, unsurprisingly, we find another lofty vision.

On the writer’s part, Buechner believed that the novel could be nothing less than a source of self-healing, blessing, and a means of gaining spiritual and intellectual insights that could not be arrived at in other ways. Over the course of his writing career, he fictionalized many aspects of his own experience, finding new forms of clarity and catharsis, but felt that he had been “blessed” most powerfully by Godric, which he took to have received entirely “on the house,” since it had arrived “unbidden, unheralded, as a blessing.”[8]

In writing the strange lives of saints, like that of St. Godric, Buechner also realized that he himself as a novelist could in fact become more like a reader, since instead of planning and controlling his characters’ every move, he would be continually surprised by their thoughts, speech, and actions. Buechner saw saints as perfectly suited to the novel, since they transcend all of the novelist’s preconceptions and refuse to be contained within conventional structures. “There’s so much life in them,” Buechner insisted. “They’re so in touch with, so transparent to, the mystery of things that you never know what to expect from them. Anything is possible for a saint. They won’t stay put or be led around by the nose, no matter how you try.”[9] Life-givers themselves, they also have an extraordinarily life and vitality on the page.

His gambit was that by encountering such luminous souls on the page, his readers would be able to more fully claim their own. The novel, as Buechner saw it, was thus capable of nothing less than making us “more alive.” If we can imaginatively enter into the lives of saints, temporarily bracketing off our own consciousness in order to take in the world as they perceive it, we may well find new sources of energy and power. “The Holy Spirit has been called ‘the Lord, the giver of life,’” notes Buechner, “and, drawing their power from that source, saints are essentially life-givers. To be with them is to become more alive.”[10]

Buechner’s idea here is that if we recognize holiness and life-giving power in someone else, we can’t help but see through to its source, the divine wellspring of which their life is just one small tributary. But Buechner doesn’t stop here: he also asks us to acknowledge glimpses of this same source in ourselves, and to prepare ourselves for the possibility of becoming more alive after our encounters with such holy “life-givers.”

Buechner’s sense of the mystery and ritualizing power of the novel is also noteworthy. He was quick to admit that much of what he himself had read, together with much of what he had experienced in his life off the page, had gone “in one eye and out the other.”[11] We do indeed forget countless details from the books we read, which can fade like dreams once the rich sensuousness of the aesthetic experience has passed. For Buechner, though, such fading matters little: the images and identifications prompted by fiction can do profound work on a spiritual level, regardless of whether we are consciously aware of it or not. Novels, he thought, are capable of doing the deep, wordless work of ritual.

Exploring the lives of saints clearly offered Buechner a way of pushing the limits of the novel form. It also offered a way of affirming the holiness of himself and others. Buechner was convinced that by spending time with a “ragged, clay-footed crowd of saints and near-saints” as a writer, entering imaginatively into their joys and sufferings, both novelist and reader would be provoked into the destabilizing conclusion that the divide between saint and non-saint might not be as great as we often assume.[12] For Buechner, we are all of us potentially able to express and “bear to others something of the Holy Spirit, whom the creeds describe as the Lord and Giver of Life.” Despite his discomfort at being himself taken for a spiritual guide or saintly model by certain readers, Buechner noted his growing awareness that there was something true in what they expressed:

In my books, and sometimes even in real life, I have it in me at my best to be a saint to other people…. Sometimes, by the grace of God, I have it in me to be Christ to other people. And so, of course, have we all — the life-giving, life-saving, and healing power to be saints, to be Christs, maybe at rare moments even to ourselves.[13]

It is worth pausing again to consider how extraordinary Buechner’s idea really is. The novelist here becomes a kind of saint, while the reader is seen as being brought into a fuller sense of their own “life-giving, life-saving power to be saints, to be Christs.” Is it possible to ask more of the novel?

There is no escaping the conclusion that Buechner’s later novels call us to be nothing less than saints, by which he means those with a desire to become more fully alive — more fully human. “Through some moment of beauty or pain, some sudden turning of their lives,” Buechner suggests, “most [people] have caught glimmers at least of what the saints are blinded by. Only then, unlike the saints, they tend to go on as though nothing has happened.” He insists that “we are all more mystics than we choose to believe, even to ourselves.”[14] Buechner here echoes the Catholic activist and writer Dorothy Day: “We are called to be saints,” Day wrote, “and we might as well get over our bourgeois fear of the name.”

***

So goes Frederick Buechner’s singular vision of the novel. Clearly, he had a profoundly idiosyncratic sense of what it might be possible to achieve through fiction. He would have his readers become none other than saints and mystics. It goes without saying that the mysterious gifts and blessings of Buechner’s novels cannot be had secondhand. These are artworks that must be experienced in all their richness and complexity. His literary “thunderbolts” need to be seen and experienced to be believed. But it is here that his most powerful and enduring work is to be found.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Thank you for reading The Buechner Review. If you would like to receive future articles in your email inbox you can sign up here.

Works cited:

[1] Kenneth Gibble, “Ordained to Write,” A.D., March 1983, 17. The critic Dale Brown, who has argued that “Buechner’s characteristic themes find their deepest expression in his fiction” clearly agrees. See Dale Brown, “An Overview of Buechner’s Fiction,” in Buechner 101: Essays and Sermons by Frederick Buechner, ed. Anne Lamott (Cambridge, MA: Frederick Buechner Center, 2016), 120

[2] Annie Dillard, quoted in Dale Brown, The Book of Buechner: A Journey Through His Writings (Louisville,

KY: Westminster John Knox, 2006), 372.

[3] Of course, they did not go entirely unappreciated in his own lifetime: Buechner’s fiction was praised by Malcolm Lowry and Christopher Isherwood, as well as by the aforementioned Annie Dillard, who thought that Buechner was nothing less than “one of our finest writers,” together with serving as her own personal “hero,” a “guide and inspiration.” And while there were moments of wider recognition in his literary career (an O. Henry Award for his 1955 New Yorker story, “The Tiger” and being a Finalist for the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize), Buechner’s novels have always been underread and underappreciated.

[4] Frederick Buechner, “Literature and Life,” delivered at Bangor Theological Seminary. https://soundcloud.com/frederick-buechner/literature-and-life-bangor-theological-seminary?in=user-411758068/sets/to-listen; Richard A. Kauffman, “Ordained to Write: An Interview with Frederick Buechner,” The Christian Century (September 11, 2002). https://www.christiancentury.org/article/2002-09/ordained-write

[5] Stanley Cavell, Conditions Handsome and Unhandsome: The Constitution of Emersonian Perfectionism (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1990), xxxii.

[6] Annie Dillard, “The Ancient Story of Jacob, Retold in a Passionate, Exalted Pitch,” Boston Sunday Globe, May 30, 1993, A15.

[7] Brown, The Book of Buechner, 372.

[8] Brown, The Book of Buechner, 225.

[9] Frederick Buechner, “Faith and Fiction,” in William Zinsser (ed.), Going on Faith: Writing as a Spiritual Quest (New York: Marlowe & Co., 1999), 60. Buechner saw Flannery O’Connor and Dostoevsky as models in the search for a form of writing that would allow for “making discoveries about holy things” (58) and in which the “nothing less than the Holy Spirit itself” (59) might have room to enter.

[10] Frederick Buechner, “Saints,” Beyond Words: Daily Readings in the ABCs of Faith (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 353.

[11] Buechner, “Life and Literature.”

[12] Frederick Buechner, “Foreword,” in Brown, The Book of Buechner, x.

[13] Buechner, The Longing for Home, 28.

[14] Frederick Buechner, “Mysticism,” in Beyond Words, 268.

Sign up here to receive articles in your inbox